by Jan Theiler

THE IMPROBABLE SOCIETY

In the late 1980’s I lived in a squat in Charlottenburg, which, with money from

the Berliner Senate, was renovated by the tenants. Before the Wall fell Charlot-

tenburg, along with Kreuzberg and Schöneberg, was still a squatter’s hotspot.

In this neighborhood, around Schloss Charlottenburg, there were 20 squats

which had either been legalized and saved, receiving lease contracts from the

city of Berlin, or were designated for eviction. The Nehringstrasse had decided

to take the official route.

We lived in massive cooperatives that encompassed entire floors of disused

flats, allowing our creativity to run free. Although the hierarchies and gaps in

everyone’s needs which appeared during this so-called self-help renovation

phase complicated the atmosphere, the stress of peer pressure and constant

planning meetings was compensated by the luxurious interiors and ability to

escape the outside world.

During this time I began to organize small readings in the bar of our house,

where I would do my best at reciting Dada-inspired poems. But in the evenings

during the early 90s it was difficult to attract an audience in Charlottenburg.

There would always be the same five locals sitting around the bar. At one point

a small group of Irish appeared, whom someone had met in the “Wild East”

and invited over for a sauna on our roof terrace. In kind, the Irish took us over

to their secretly squatted Prenzlauer Berg flats, which had been abandoned by

the original tenants, half of whom had fled to the West. Dave, a fine young man

from Dublin, took me on a crisp clear February morning to the “Schliemann-

cafe”, where everyone from the neighborhood would sit around a massive wood

stove and drink cheap East German beer, enjoying a recess from their squatted

flats because none of them had functioning heat.

The LSD block, as it was called, was named not after the psychedelic drug,

although there was plenty to be found there at the time, but because the paral-

lel streets were named consecutively Lychnerstrasse, Schliemannstrasse, and

Dunckerstrasse, with the disreputable Helmholtzplatz lying in the middle. It

was in the overheated Schliemanncafe, where riffraff paraded about through

smoke in secondhand fake fur coats, sweating profusely, that I met Divo for

the first time. He went by the name of Hackepeter, a term used for a Berliner

specialty of ground raw pork. I remembered the commonly used phase: “From

Hackepeter comes much shit later”. Was this the basis of Mak Divo’s nick-

name? In a crowd of shady drunks he gave the impression of being a closet

intellectual. My Irish friends introduced us, then Mark lead us quickly to Dun-

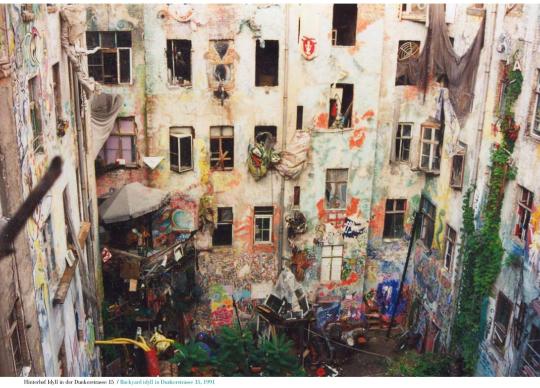

kerstrasse 14/15, where the so-called Improbable Society was housed. Here,

walking through their inexhaustible arsenal of junk from the recently extinct

GDR, where hoards of artists had transformed the ruins and seemingly endless

courtyards into daring sculptures and labyrinths, defying the rules of the eve-

ryday world, my life would change forever. I quit working on my degree in art

education, moved out of Charlottenburg, took over Dave’s squatted flat in the

LSD block, he having to return to Ireland, and realized my plight as a probable

in the Improbable Society, increasingly intoxicated on its vagaries. I was part

of a living, mutating museum and no longer felt a need to collect certificates

of stuffy theory.

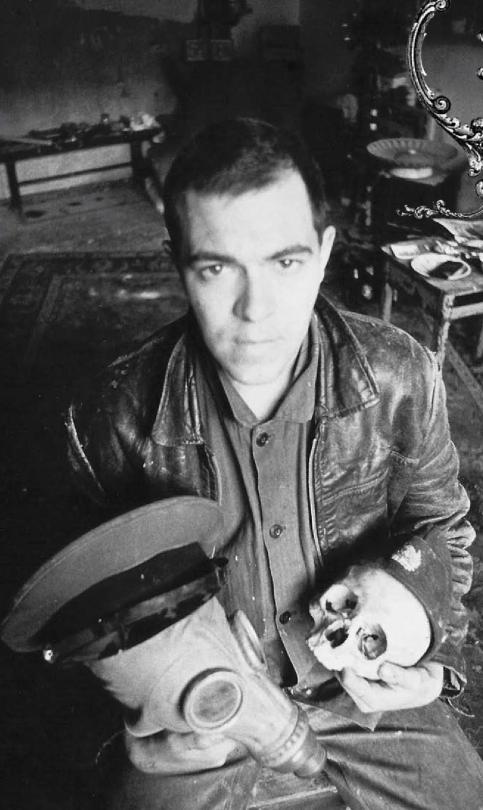

Among the members of the Improbable Society, who had seemingly and

permanently severed themselves from bourgeois comforts and mores, Mark Divo captivated everyone with his impiety and subversive ingenuity. Nothing

seemed more ridiculous to him than wasting one’s life in a meaningless con-

ventional job, earning a living but never being able to contribute to a major

change. In that sense to fail as an artist was not an alternative. The disrespect

for his middleclass background and the human tradition of betrayal and ex-

ploitation in general, of which he had a sheer unending knowledge, allowed

him to concoct new strategies and means to avenge society. Ridicule what

ridicules you.

In the Dunkerstrasse neighborhood the petty criminal free spirit of my

bourgeois cowardice would be liberated. The people here were experiencing

a certain unkempt dignity, stricken with Merz-Bau fever, building bars out of

stolen gravestone. Here, Pastor Leumond was born, and Mark Divo was the

midwife and amanuensis.

I articulated my ideas to him about holding an interactive reading choreo-

graphed as a sermon. He quickly offered a dome, already under construction,

made of plastic toys, papier-mâché and junk bound together with cable, as

my chapel. I decided to take the crypt-like room next door, which being two

stories high because the floor had caved in to the cellar below leaving only

tiny remnants of the floorboards leaning on a pile of rubble, providing a place

for the pulpit. He heartily reminded me the most important part of the perfor-

mance was the collection tray, which I constantly forgot, driving Mark nuts to

this day.

The ceremonial chamber Mark provided would later be used as the parish

disco, where every Thursday at about two in the morning, after the sermon,

my ever-growing congregation held court to hits from the 70s and cheap beer

from Czechoslovakia, providing me and tender acolytes with financial support.

After two years, the residents, angry about the churchgoers pissing on their

sculptures in the yard, put the kibosh on my chapel by sealing it with never-

drying typewriter ink from the GDR. Concomitantly the Improbable Society

disbanded, leaving Stumpfsinn as the forerunner. Pastor Leumund performed

a massive baptism at a squatted castle in Zessen, plunging suckers deep into

a Brandenburger pond.

I was living in a Kastanienalle do-it-yourself commune under construction

when Mark Divo slipped from my attention. I heard of a party he put on in the

Fischlanden, where he handed out free beer all night long because he had

foiled a film crew shooting a scene in Friedrichshain using a squat as a back-

drop by hanging a massive swastika flag out the window and demanding pay-

ment if the film crew wanted it removed. He then returned to Zürich leaving

the city with only the wildest rumors of Hackepeter’s darkly sarcastic antics to

spread from house to house.

KRÖSUS – FOUNDATION 2002

Ten years later, Charlottenburg works against the newly sanitized East Berli-

ner center almost whole-heartily. Any type of occupation, or attempt to squat,

is quashed by undistinguished policemen. The do-it-yourselfers finished their

degrees and had children. The LSD quarter is ruled by P.C. hippies boasting

the highest birthrate in Germany, and Kastanienallee is renamed Castingallee.

I had moved back to West Berlin and was working as a newspaper reader. Eve-

ry morning at half past three I would search for media watchdog agencies like

a human scanner, combing through meter-high piles of newspapers in search

of company names, so that managing directors might have their press releases

and competitor’s press releases on the breakfast table to examine by daybreak.

I would go back to sleep by noon, losing most of my social contacts. My girlfri-

end, who’s flat I lived in, is at the end of our rope. The telephone rings, and I

set down a week-old croissant on the floor. Mark is on the other end, asking if I

wanted to participate in a planned squatting of the old Caberet Voltaire.

I could make a better living as an artist in Zürich than in Berlin. Toying

with thoughts of beautiful women, I pack my bags and arrive in Zürich the

next day.

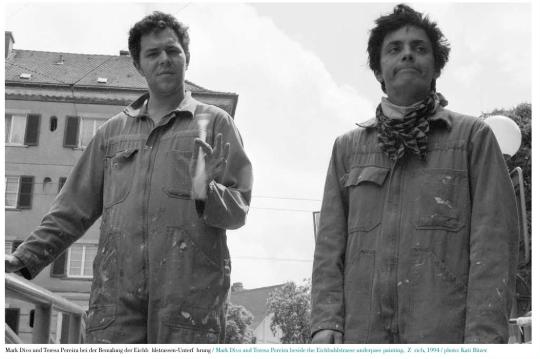

It had been ten years since Mark Divo left Berlin, but there had been several

occasions to meet. Berliner artist squatters visited Zürich squatter artists and

visa versa. Once a bunch of activists camouflaged themselves as a “Conference

for Security and Freedom”, which unfortunately ended sooner than planned.

Mark Divo appeared with a FDP propaganda stand and was genuinely ready

to pose as the FDP’s district group leader in front of the deviously real Swiss

security guards protecting the entrance. We also, together with an international

cadre of lunatics, put in a month-long party in Zürich’s Eschrwyss-underpass.

We met at festivals in Copenhagen and Genoa. This time I don’t come because

of a festival. I come to stay.

Mark and I share a couch in a living room with a family and their three kids,

in Kreis 8. The most spectacular unused site and the artist hoards to squat it

would come together in Niederdorf in three weeks. Until then I have a lot to

learn. In contrast to Berlin there was a growing squatter generation in Zürich

that is more nomadic, moving around from site to site instead of entangling

itself with cooperatively buying a disused building or even pursuing revolution

for that matter. The Berliner zero-tolerance law is the total opposite in Zürich,

where after the occupation of a vacant building the owner has to provide con-

crete plans of redevelopment before any action against the squatters could

proceed. It is estimated there are 30 squats in Zürich, occupied by a politically,

hedonistic and artistic factions who for the most part peacefully intermingled

or tangled with one another. Mark Divo alignes himself with all of the factions,

sometimes against their will. Through his contacts, experience and refractori-

ness he is always remaining a ringleader. He is decisive yet a fusion reactor at

the same time. Under his lee Zürich is home as long as one doesn’t feel rolled

over by his restless machinations.

I live with Mark in a relationship where we spent every day together. Every morning

he lures me out of bed with fresh croissants, then leads me through a tightly plan-

ned schedule. I am the maid, the secretary, filling out applications and composing

manifestos, lugging boxes around, driving rented transport vehicles, and engaging my

not inconsiderable diplomatic skills each step of the way.

During the week before the Cabaret Voltaire is to be squatted, we drive conti-

nuously to a huge charity shop outside the city to collect together supplies for our

future Art-Nomad Sect. We haul mountains of carpets, mattresses, dishes, antiques

and organs. In the years to come, these trips would incessantly repeat.

On February the 2nd, in thrown-together eveningwear, squatters colonize the Ca-

baret Voltaire, offering coffee and snacks to a gaping formation of policemen, accom-

panied by the din of Mark’s gramophone record collection. For years the abandoned

building of the historic birthplace of Dada had only a well-hidden plaque reminding

us of its history. The missing plans for a renovation of the property and Mark Divo’s

close relationship to the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs make the preliminarily

tolerated Dadaistic revival feasible. From then on the building was packed night after

night with festive tinkering artists and tourists who were feverishly smashing together

a combination of the possible and impossible, cultural and commonplace operations.

In the early hours of the morning when they are finished Mark and I would throw the

drunks out into the street and lock the door from inside.

We live together with twenty hedonistic anarchists in the top stories of the buil-

ding, at the same time creating a place for traveling artists and partially rehabilitated

petty criminals to stay.

Internally, Mark enjoyes confrontation. At a house meeting, when an argument

careened to the point of utter disgust, Mark burnes a 100 Swiss franc note earned

from entry and beer sales in front of everyone’s eyes. During a day of Dadaist ac-

tion called forth by the collective presenting in the commons a Isola delle Femmine

concert, a Lima octopus fishing contest, and milk showers, Mark’s contribution is to

drink expensive champagne in the city’s finest restaurant. Collaborating with him in a

squatting and/or artistic enterprise is always a trifle unsettling.

His polarizing name draws all of the attention to himself and quickly dominates

and devours shared activities, a recurring narrative that serves to prop up the group.

Many feel excluded. Most collaborators profit from Divo’s unceasing intrigue and his

ideas, from which emerge free rooms where artists may work, find shelter and exhibit

creations unmolested. Despite many warnings, e.g., “The Swiss are too up-tight for

that,” our Dadaistic activities at Cabarat Voltaire are well-received.

The Züricher always seems to feel a need to set himself free from what the Zwingli,

just less than a few hundred meters away in Grossmünster, conjured up after centu-

ries of forced renunciation and pressure from the Reformation. Every Saturday at

about midnight, in Niederdorf, parishioners sing, pray, and screame in confession as

if bound in ecstasy. I suppose in our spiritual torpor we were conciliar reformists.

After three months of nightly experiments, in between Post-Dadaist pilgrimages

to every corner of the world, the socially plastic, mutates Cabaret Voltaire teetered

at the verge of eviction. Early each morning we park the smallish transport van at

the delivery entrance of a charity shop and stuff it with tons of books with which to

barricade the windows and doors of Cabaret Voltaire. Inside, we establish the Krösus-

Foundation, which prescribes the squandering of derelict resources and an increased

occurrence of throwing money out the window during speeches. During the final night

of the squatted Cabaret Voltaire, the Krösus-Miliz-Army was formed amid a spontane-

ous mass creative activities orgy. The day of the scheduled eviction, the Dada mob

attacks Zürich’s inner-city police stations with an arsenal of cardboard tanks, pikes

and machine guns (Dadadadadadadada), and installes an oversized gauntlet at one

of the precincts. Concomitantly the building workers, contracted by the city, toss the

entire inventory and art collection of the Krösus-Foundation into a bevy of dumpsters.

Again I sit on the streets with Dada squatters in unlawful assembly. But during

my stint as Program Coordinator of the squatted Cabaret Voltaire I met hundreds

of artists and musicians from Zürich, whose couches I would always occupy.

Because of the occupation, the city of Zürich uses the newly awoken interest in

the birthplace of Dada to re-launch Cabaret Voltaire as a commercial enterprise,

along with help from Swatch, on its own terms. A Dada Swatch watch was re-

leased. A souvenir shop is opened, together with an exhibition of flat screen TVs.

A tourist bar appears where speaking is kept to a sotto voce because, through

cross-financing, the upper stories are being developed into condominiums and

sold to wealthy Americans. Reality becomes much more Dada-like. Arnold

Schwarzenegger is elected Governor of California.

Vultures swoope lower, a swan fell from the roof, and no one thinks to ask,

“How many unpaid fingers have crocheted Mark Divo’s balaclava?”

We are compelled to find an authentically Dadaistic counterargument. Well-

bathed and boarding Zürich trams in pressed tuxedos and bowler hats, giving out

free champagne to the known fare-dodgers, we organize demonstrations with the

recurring chant, “Ignore us.”

We walk daily for hours through Zürich’s residential neighborhoods with a

magnifying glass, searching for vacant properties. After several months we spy a

new home for the Krösus-Foundation. In the empty, four-storey villa of the Uni-

versity of Plattenstrasse, the Dada Fundus would reunite from all of its camps

spread out across the city and flourish over the next two years.

The dissolution of borders between the private and the public in this living

sculpture can finally be explored again. The window of opportunity stands wide

open for the nerds of the city.

Mark always comes up with new ways to profile himself, as artist and instiga-

tor nourishing the spirits of his loyalists. Whoever pays rent during these times

in Zürich had only themselves to blame. Whoever is in need of money can build

a bar in between the art installations. During the occupation in Niederdorf the

beer consumed leaves mountains of empty beer bottles in the cellar of Cabaret

Voltaire. Mark removes them to the Helmhaus-Museum, winning a grant in New

York with this smelly installation.

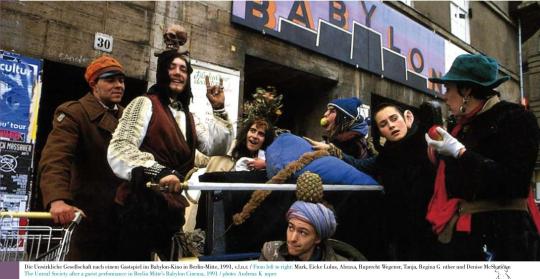

The staged photographs of neo-baroque classical parodies, the sales of which

are unjustifiably rare, that hang in the Museum Platte in large gilded frames,

Mark Divo and his cohorts present to the public dressed in classical costumes

consisting of second-hand synthetic fiber garments augmented by showroom

dummies that look like sculptures from the ruins of an ancient temple but made

of Styrofoam.

Mark and I grow close to Zürich’s Housing Bureau for Seniors, hoping to gain

support for a cross-generation project using the community meeting hall of the

Senior Home to produce staged photographs of aging women. In addition, we

frequently write grant proposals that concentrated on financing a week-long Dada

Fest which, since the occupation of Cabaret Voltaire, takes place each February

in Zürich, thus allowing us to invite our cronies from Zürich, Berlin and the rest

of the world to take part. Just as the money is about to run out, we rent limousi-

nes and dumpster-dive in hand-picked supermarkets, in quest of freshly expired

gourmet products.

Though Mark and I have fundamentally different temperaments and conflic-

ting motivations, these are wet-blanketed and doused by a common interest in

collective chaos, making us inseparable. He would rudely awaken me each mor-

ning, constructing master plans. He throws me a ten frank note from the kitty

because I had to fetch croissants. The kitchen is constantly populated by visitors

from Berlin. My room has become the Dada commune office. At my computer

sat day and night chain-smoking creativity. More and more I flee to Mark Divo’s

chambers and lull around with him in bed, which can only be reached after one

overcomes the mountains of skid-marked underwear, moldy teacups and all sorts

of beginnings of little art projects. Mark pulls one black booger after another from his nose,

swallowing them with pleasure, to the incessant clang of Rondò Veneziano. The record is

glued to the record player, bought at a flea market, by a brown liquid that had been spilled on

it long before. Here, no one else dared to venture. He sometimes entertaines his experimen-

tal desire for beauty by writing Knicks poems or sticking collages together. He would then

throw on his bathrobe and offer the guest black tea, fags and marijuana cigarettes.

Mark’s pet peeve is the problematic artist who tears out his hair just to get his lowly

works legitimized so that curators might jam spiritually desolate museums with it.

For the opening of an exhibition encompassing the entire ground floor of the Platten-strasse, Mark and I take a guide from the current exhibition at the Zürich Kunsthalle and change some of the words: “In an expansive installation filled with subliminal allusions, the Platten All-Stars have found that petty objects are shit. A worn remote control, shaky attitudes and a disused dildo are the protagonists of this screenshot. A patina of stench, passion fruit and arbitrariness covers the furniture and infects the history of its use. Stylized squamous cell carcinoma, incense and a long-expired accident insurance policy resurface like fried found objects of a still life. A sentimental aura of the forgotten past surrounds an object that triggers the soul’s latent inner conflict. The earliest group work of the Platten All-Stars discusses abstract social operations and points to how a single person constrained by social and political processes may transform into an object of desire and thus transcend the system. At closer reflection, the installations appear brittle and inaccessible, showing themselves as probable contraceptive devices in precise arrangements of misunderstanding. With finely drawn traces of blood, phrases like “between hysteria and house plants”, “the slow lane of daily drudgery”, and “practicing doctors dance naked” added glue-like zeal to our collective agenda.

The Platte Museum burst out of its seams. The zenith of the Dada- occupation was still to come. The massive factory grounds of Sihl Paper stands empty for many years, leaving huge industrial halls to lapse into junk shops for accumulated goods. This is where the second Dada Fest and subsequent four-month occupation by the unreal Art Squat of the Superlatives would be housed.

Mark and I hold a meeting with the sympathetic President of Zürich’s Department of Culture, who permits us to sign a sort of contract in which we are not responsible for explaining the forthcoming occupation. In the months to come, this mop would cause me

many sleepless nights, fearing that, during the week, a policeman might take one look at the Fest.

The place of the Happening has to be kept secret. After that, we would lure visitors to the Plattenstrasse, where they would be greeted by a swing orchestra from Berlin and witness the live broadcast of the squatting of the factory. On the first night, Zürichers storm the event by the thousands. Due to the extraordinary number of people, the industrial halls took a long time to become accessible. In sub-zero temperatures, newly arriving Berliners, who are hanging about, decide to cobble together fortifications and collect together laundry basket loads of Swiss Frank notes as tithes. At five in the morning, I stuff it all in my pockets and bunker the money under my bed. Later, I hand it out to the traveling musicians and performers. The stage hands, who sprang up from unending spaces like glow-worms, also have expenses that need to be covered—tough titties. Then I purchase croissants for everyone, taking the rest of the money and depositing it into the account of Krösus-officials. Mark Divo is only to be

trusted to spend the money in private, on champagne and prostitutes.

First, there are the concerts and theater halls. Then came a media lab for digital artists, a Robot-Forge, a climbing park, a haunted train in the basement, a futuristic lounge with roof garden, a travelers’ site, several artist studios, adventure bars, and dance halls as well. While Mark opens a section of the museum with over-sized installations by newly befriended artists, I purchase as many second-hand roller skates as the city had to offer and organize a roller disco in the opposite hall, where one can skate back and forth between the factory

floors along internal wooden causeways. The squatted Sihl Paper is a city within a city, bursting with of innumerable delights from which all levels of Zürich society were running about, contorting their lips.

The large Zürich construction company that wanted to build a shopping mall on this site is paid a hefty fee by the city for the maintenance of the building because of the massive contamination that had developed after the city tolerated the Dadaists on the premises. The Dada squatters are of course considered Dada vandals now.

Directly after the eviction of the factory area, in the summer of 2003, the Dada vandals and their dangerously swollen collection or carpets, furniture, and sounds systems squat the Heimplatz in front of the Kunsthaus. Prominent forward-thinking punks from Hamburg, who are enjoying a sort of business-related living asylum across the street from the theater, came over to participate in the social sculpture.

During the cacophony of the homeless artist-ravers jamming with Erobique on the organ, always dominated by Mark Divo’s useless rants, Rocko Schamoni falls from an over-sized rocking horse and sustains an injury to his privates.

With the lack of vacant properties, the Dada collective slowly falls apart. The Krösus-Foundation still organizes festivals in Zürich in public toilets and porno-cinemas, but finally emigrates to foreign countries.

We never got rid of the dada-label again. It seems to me, that everything that falls out of alignment, everything funny, that doesnt deal with knee-slapping humour and predictable payoffs, everything, that doesn’t want to be reasonable at

once is called dadaistic in these days, because there is no other word for it.

Though we lived in Merz-installations, dadaism is an insufficient description of our doing, even if this term was strategically clever for the squatting of the Cabaret Voltaire and quite helpful to characterize the sermons. But actually we conducted the devaluation and abolition of art even more consistently than its forefathers Ball

and Arp did. We opposed the demand for an unleashed individual of the avantgard in the beginning of the 20th century with the corrosion of the individual by working collectively. We were seeding confusion and harvested free space.

In our temporary cultural centres we created usable total artworks, where vistors became a part of a mutating installation, allowing a sensual and playful access to art.

Therefore we dismantled the aura of contemporary art systematically. Everybody who wanted, was able to exhibit or perform in our place. We completed the slogan of Joseph Beuys, saying „everyone is an artist“ with „everyone should get his own museum“.

The negation of the white cube put a special task on the participating artists, whose artworks had to stand up to furniture and paintings from the trash and the thunderstorm of sound coming from 20 home organs.

Mark Divo pretends that the motive of his art is to be paid for idleness and to produce gold out of shit, i.e., alchemy in its truest sense. But idle is precisely what Mark Divo is not.

Mark Divo surely is a master in recruiting assistants, who materialize his ideas, but he is not able to do nothing. There is always something in his mind or in his hands that is connected to the next project. Holiday? – an alien concept to him.

Mark Divo relaxed in a hammock? – unthinkable. His passionate honor system was always a trigger for hostilities with his politically correct peers. He lived together

with them and distanced himself from them passionately in the same time. He did not just provocate the squatters`s scene with his Biedermeier-Nazi-dress over

decades but also insisted to open occupied houses with the help of art and contributed to the fact, that the myth about the grimly looking squatter started to gather dust and the bourgeoise press lost it ́s enemy stereotype.

Whoever calls him an egoist or money-grubber should visit Kolin and see for themselves what a sound investment he has made with mooched infrastructure. For sure, he doesnt spend his money in cocaine, fancy cars, winter-sports, holidays in Gomera or psychotherapy dates. He continues to be the hyperactive guar-

dian of an art underworld. That makes more sense to him than protesting against gentrification.